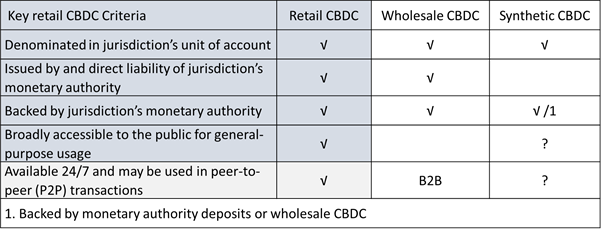

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a broadly available general purpose digital payment instrument, denominated in the jurisdiction’s unit of account, that is a direct liability of the jurisdiction’s monetary authority. To this I would add, subject to the same rules and regulations as imposed on the jurisdiction’s other units of account. By “general purpose” is meant that it can be used by the public, for day-to-day payments rather than CBDCs restricted to wholesale, financial market payments. A liability issued by a monetary authority that is not in its own currency (i.e., where it does not have monetary authority) is not a CBDC. I’ve summarized this definition in the table below and have added that it can be used for peer-to-peer transactions, which the Banque de France also views as an essential characteristic.

In previous versions of this tabulation, I included legal tender status as a key characteristic. A currency’s legal tender status entitles a debtor to discharge monetary obligations by tendering the currency to the creditor. However, a recent IMF working paper casts doubts on whether a digital currency can, or even should be given legal tender status. For example, designating CBDC as legal tender is not obvious if broad layers in the population are not positioned to technically receive it as a means of payment (e.g., not owning a computer or smartphone). Legally, it may not be possible either, because the creditor without access to the technology cannot accept the payment even if she wants to.

Anyways, this is the definition I’ve been applying to my real-time tabulation of retail CBDC explorers, but I frequently get suggestions to add new entries that don’t fit my definition. However, many turn out to be clearly wholesale CBDC, which are easy to identify and reject. And there are several more subtle ones that pop up, such as the Republic of Marshall Islands (RMI) SOV, and Cambodia’s Project Bakong, that I will briefly run through here. The SOV is easy to reject because there is no RMI monetary authority, and it is not denominated in the country’s unit of account, which is the U.S. dollar.

Cambodia’s Project Bakong has been sometimes called a quasi-form of CBDC but from my read of the white paper, it is arguably at most some form of synthetic retail CBDC. To me it appears to be a central bank-run interbank retail payments system that runs on distributed ledger technology rails that requires that any user balances be parked at the central bank. That makes it possibly a synthetic CBDC, in the same way that China’s AliPay and WeChat Pay are because they are required to park user funds at the People’s Bank of China. But in all these cases, the digital currencies are not issued by and direct liabilities of the central banks, so they’re not CBDC.

And the National Bank of Cambodia’s Chey Serey would seem to agree that Bakong isn’t a CBDC. “Instead, the platform augments the existing Fast and Secure Transfer (FAST), real-time retail payment system and Cambodian Shared Switch (CSS) that facilitate mainly interbank transactions among commercial banks and MFIs. They were launched respectively in 2016 and 2017 and are Cambodian riel (KHR) and US dollar account-based systems that do not interoperate with the twenty or so PSPs that serve mainly the unbanked. With the launch of Bakong, banks, MFIs and PSPs have a ready-made universal mobile app interface to connect users with FAST, CSS and each other.”

However, I have been long maintaining the Banco Central del Ecuador’s Dinero Electrónico mobile payment system in my CBDC explorer tabulation but being somewhat uneasy about its inclusion. The program, which operated between 2014 and 2018, allowed citizens to transfer USD balances in real-time from person to person using basic cell phones. From my read of a recent paper on the Dinero Electrónico it would seem to be a central bank-run USD asset-backed stablecoin. Like with the RMI, the USD is the country’s unit of account, but in this case the digital currency is indeed denominated in Ecuador’s unit of account, and it was issued by, and a liability of, the central bank. Hence, it’s a CBDC by my definition.

However, Marcelo Prates has suggested that digital currencies like the Dinero Electrónico is nothing more than a stablecoin issued by a central bank. Basically if the central bank can’t issue traditional money (reserves + cash), it can’t issue the “digital” version of this money. Hence, by this logic, only central banks that issue their own currency can issue CBDC, which precludes completely dollarized country central banks from issuing CBDC. Besides U.S. territories, these include Ecuador, El Salvador, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau, Panama, Timor-Leste, and Zimbabwe. The same would go for countries in the eurozone and other currency unions. But would countries with currencies anchored to another country’s would still be able to issue CBDC?

BTW some might note that I don’t include in my tabulation the Avant smart card system created by the Bank of Finland in the 1990’s that was the world’s first CBDC. It is indeed a CBDC, but my tabulation seeks to cover CBDC projects that are potentially still live, whereas Avant shut down in 2006. However, I have added a new section to my tabulation for retail CBDC projects that have been shut down.

In that regard, I’m tempted to drop the Banco Central del Ecuador’s Dinero Electrónico from my CBDC explorer tabulation because it is now similarly defunct, and it is questionable whether the Ecuador central bank can even issue a CBDC. But alternatively, I could include the Avant as a CBDC that has launched/ piloted. Any thoughts out there?