One of the first big retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) design decisions is the operating model. In a single-tier model the central bank performs all the tasks involved, from issuing and distributing the CBDC to running user wallets. In multi-tier models, the central bank issues and redeems CBDC, but distribution and payment services would be delegated to the private sector. Which model to adopt will depend on country-specific circumstances, such as financial sector breadth and depth, financial integrity standards compliance, and financial market infrastructure availability and supervision capacity.

Single-tier models

In a single-tier model, CBDC transactions resemble transactions with commercial banks, except accounts would be held with the central bank. A payer would log in to an account at the central bank through a web or mobile application and request a transfer of funds to a recipient’s account, also at the central bank. The central bank would ensure settlement by updating a master ledger, but only after verification of the payer’s authority to use the account, enough funds, and authenticity of the payee’s account. This mode gives central banks more control over the product design and implementation process.

However, the single-tier model requires the central bank to assume an active role in distribution and payment services that may exceed the scope of its core mandate and capacity. Moreover, central banks would directly compete with existing digital payment service providers creating disintermediation risk. Conceptually, the single-tier model may be appropriate for a country with a well-resourced central bank in which the financial sector is extremely underdeveloped, so that there are no institutions to assume distribution and provision of payment services, as may be the case in some low-income countries.

Multi-tier models

In multi-tier models, the central bank issues CBDC but outsources some or all the work of administering the accounts and payment services. However, CBDC remains the liability of the central bank and thus CBDC holders would not be exposed to default risk of the engaged payment service providers (PSPs).

The multi-tier model has been the overwhelmingly preferred solution in CBDC pilots and the only launch so far. Running currency distribution is not something the central bank is well-suited to perform, requiring customer-facing activities that may be beyond their capacity. Also, the multi-tier model is less disruptive than the single-tier one as financial institutions play their traditional roles in distribution and payment services. In addition, this layered approach facilitates the integration of new types of consumer electronic devices without the need to alter the core of the system, and it supports the ability for third parties to build on top of the core (Shah and others, 2020; Armelius et al, 2021).

Different Flavors of Multi-Tier

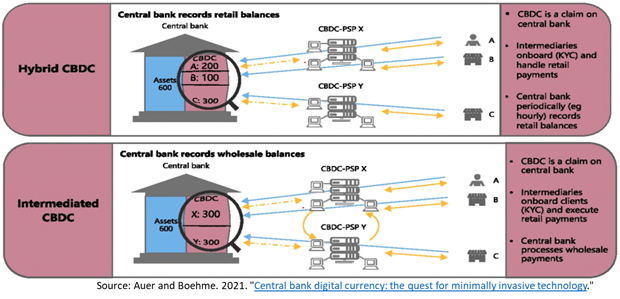

Auer and Boehme (2021) discuss two different multi-tier models that differ in terms of the records kept by the central bank. In a “hybrid” architecture the central bank records all retail CBDC holdings and the CBDC is never on PSP balance sheets so that user holdings are not exposed to claims by PSP creditors in the event of PSP insolvency (first panel below).

In an “intermediated” architecture the central bank only runs a ledger of PSP wholesale CBDC holdings (second panel). Central banks may prefer this architecture due to privacy and data security concerns. However, the central bank still must honor CBDC holder claims in the event of PSP insolvency or data breaches, relying on the integrity and availability of the PSP’s records. This will require close supervision to ensure that the wholesale holdings add up to the sum of all retail accounts at all times.

Auer and Böhme (2020) suggest that, in an intermediated architecture, there be a legal framework that keeps user CBDC holdings segregated from PSP balance sheets so that the holdings are not considered part of a failed PSP’s estate available to creditors. They also suggest that the legal framework could give the central bank the power to switch user accounts in bulk from a failed PSP to a functional one. To do this expeditiously, the central bank would likely have to retain a copy of all retail CBDC holdings.

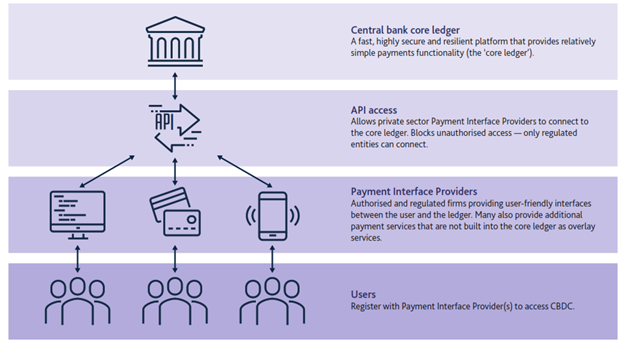

Bank of England (2020) proposes running a hybrid architecture on a “platform” in which the central bank provides a fast, highly secure and resilient technology infrastructure to provide the minimum necessary functionality for CBDC payments (the “core ledger” below). Payment interface providers would connect to it via an application programming interface (API) to provide customer facing CBDC payment services. This model effectively “combines indirect connection to the central bank with direct access to the central bank balance sheet and the CBDCs.” (Prates, 2020)

Overarching Multi-Tier Model Considerations

The multi-tier CBDC ecosystem should be designed to create economic incentives for PSPs to participate in ways that serve central bank interests (making the CBDC broadly available to the public, across regions, etc.). There should be a cost-effective business model for such PSPs with enough revenues from interest spreads, fees, and cross-subsidization, as well as controllable fixed and variable costs. Also, regulations should leave room for enough users to reach critical mass and incentivize network buildup while promoting PSP market competition.

For example, regulations that encourage interoperability of competing payment systems to encourage new entrants and reduce concentration risk should take care not to adversely impact network build-up. (For a new PSP, interoperability across PSPs could diminish the incentive of a startup to innovate since it could lower the value of a privately developed network. It could also restrict competition by excluding certain technical innovations or restricting new business models and reduce the value and increase the costs to PSPs. In addition, interoperability might increase overall risks if an innovative service provider has a higher risk profile.)

Arturo Portilla: I don’t think existing antitrust doctrine and precedents support the following statement:

“For a new PSP, interoperability across PSPs could diminish the incentive of a startup to innovate […]. It could also restrict competition…”

Kiffmeister: Which part(s) of the statement would not be supported by antitrust laws and doctrine? (1) “Interoperability across PSPs could diminish the incentive of a startup to innovate since it could lower the value of a privately developed network.” or… (2) “It could also restrict competition by excluding certain technical innovations or restricting new business models and reduce the value and increase the costs to PSPs.” And how/why? (2/2)

Well, both, actually. Extensive antitrust and economic studies have concluded that increased competition leads to more innovation (including the need to create new business models). Regarding the first point, specifically, it has been widely concluded that the existence of Many players in any given market, is a signal showing that such market offers decent margins and profitability. So, the fact that there’s competition does not imply a market is less attractive.

Although it might lower the barriers to entry, wouldn’t forced interoperability diminish the incentives for new entrants by limiting the scope for new and profitable digital wallet platforms?

Not really. I understand why the possibility to become a walled garden monopolistic monolith is attractive, specially for VC investors, but not being a monopolistic monolith doesn’t mean there’s no opportunity to make money.

So what you’re saying is that there could still be opportunities for new entrants to offer new digital wallet platforms with improved user experiences that could profitably snatch business from incumbents.

Yes. To the extent barriers to entry are not overly burdensome, regulation is suitable for entrants and incumbents avoid engaging in monopolistic practices. — Entrants can always adopt new technology and test alternative business models faster than incumbents.

LikeLike

Marcel Prates: Can’t we find a way to preserve the benefits of a direct CBDC while reducing its downside? Yes, we can. A good example is the platform model proposed by the Bank of England earlier this year (not the so-called hybrid model).

In this model you still find intermediaries between the central bank and the public. However, these intermediaries are not offering a balance sheet to hold people’s digital money. They provide instead technological tools to help any person or business connect with the central bank and access the digital money kept there.

In short: the platform model combines indirect connection to the central bank with direct access to the central bank balance sheet and the CBDCs.

This type of CBDC could promote innovation and boost public-private collaboration in the monetary system. The central bank would continue to be responsible for the monetary infrastructure, making the payment system work and setting money accounts for everyone, not just banks. This would also make the distinction between “wholesale” and “retail” CBDC redundant: it would be the same CBDC for all.

More than that, the central bank would have to ensure that this infrastructure is not only safe and resilient but neutral and open. The goal should be to allow different types of software that meet performance and security requirements, the “application programming interfaces” (APIs), to access the payment system’s data and functionality.

https://www.coindesk.com/policy/2020/10/26/the-big-choices-when-designing-central-bank-digital-currencies/

LikeLike